Over the last two decades Dr. John Chia, an infectious disease specialist, has painstakingly built an evidence base for enteroviral causation in myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME). In a comprehensive interview done by Amy Proal PhD, cofounder of PolyBio, he discusses the circumstances that introduced him to enteroviruses, the historical outbreaks of ME as being potential outbreaks of an enteroviral pathogen and his own patients and experiments concerning the role of enteroviruses. Indeed, as the previous sentence suggests, it is a lot to unpack but the interview is very important for those who have the stamina to watch it.

Interview Link: https://youtu.be/LSucgoEvoUQ

For those who get overstimulated by too much sight or sound I also wrote an outline which, I believe, is fairly comprehensive: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1jroQ3otaUZ4MuwPuKY3ELIaSmXdsPa0UoSsNmACaQoM/edit?usp=sharing

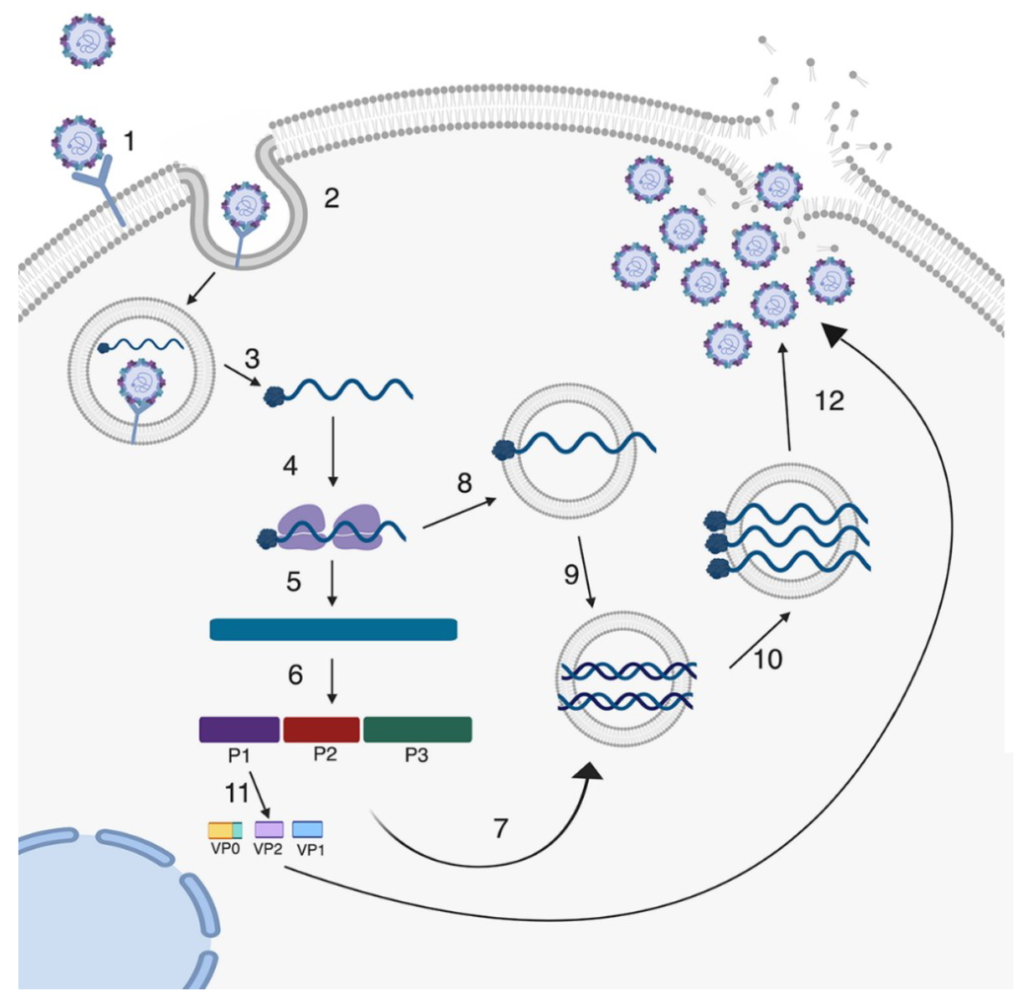

Lifecycle of A Lytic Enterovirus Infection of the Cell

Chia has fulfilled Koch’s Postulates for Enterovirus in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis

The most exciting bit of the interview for many will be Chia’s experiments on enteroviruses gathered from patient samples and their outcomes. To my knowledge, parts of this work haven’t been published in scientific journals–possibly because of the unjustified hostility many journals have to this disease (why is a topic for another time). In the interview, Chia mentioned journals often referred to ME or CFS as a psychiatric disease. A paradigm change is clearly necessary.

If taken as a whole and proven reliable, Chia’s work would show enterovirus fulfill Koch’s postulates, the classic gold-standard for identifying disease-causing pathogens [2].

- The microorganism must be found in abundance in all organisms suffering from the disease, but should not be found in healthy organisms.

- The microorganism must be isolated from a diseased organism and grown in pure culture.

- The cultured microorganism should cause disease when introduced into a healthy organism.

- The microorganism must be reisolated from the inoculated, diseased experimental host and identified as being identical to the original specific causative agent.

The most well known of Chia’s experiments was his finding enterovirus protein in the antrum of the stomach of 80+% of myalgic encephalomyelitis patients tested and viral RNA in one third (33%) compared to much lower rates for controls [3]. These results are consistent with the first postulate.

He has now expanded on this by growing the enteroviruses he recovers from stomach biopsy samples in cell culture. According to Chia the viruses form a non-cytopathic infection. This would fulfill the second postulate.

When the solution from these cell cultures were injected into immunocompromised (SCID) mice the mice infected went on to develop illness and two died. None of the mice in the control group, which were infected with boiled viral solution, got sick. In the mice that got inoculated with live virus 70% had positive infection by tissue staining of organs such as the brain and heart. Additionally, Chia was able to find viral RNA in the heart of some of the mice injected with the virus. Showing that the recovered material from patient samples was still capable of causing disease in the absence of an additional factor would fulfill the third postulate (at least as I understand it) or go a way towards fulfilling it. [4]

This experiment with inoculated mice, which was very time-intensive for Chia and his staff, also fulfills the forth postulate as they found enteroviral RNA identical to the RNA in their original cell cultures in the mice that died.

Another very strong proof of enteroviruses being the causal agent of many cases of myalgic encephalomyelitis was that Chia was able to find viral protein in the brain of a patient who died by suicide. [5]

There is a history of association of enterovirus with ME

While confirmation of Chia’s results from other researchers is needed, one of the things that many new patients may not know is there is a long history of enteroviruses and ME and they were long under suspicion by many of the early, and premier, investigators.

Indeed an article in 1990, including renowned clinicians Elizabeth Dowsett and Andrew Melvin Ramsay (one of the lead investigators of the 1955 Royal Free Outbreak) posits non-polio enteroviruses as a likely cause of ME, with the authors finding ⅓ of patients had evidence of recent or active infection by antibody titer [6]. They conclude:

“Clinical, laboratory, and epidemiological data support the suggestion that ME is a complication in non-immune individuals of widespread subclinical NPEV [Note: Non-Polio Enterovirus] infection.”

–Elizabeth G. Dowsett, A. Melvin Ramsay, et al.

Byron Hyde’s new book, Understanding Myalgic Encephalomyelitis, details several early outbreaks of ME which were associated with enterovirus and substantial evidence accumulated by Ontario health authorities of enteroviral infection in those acutely ill which peaked in the late 1980s [7].

Behan and Gow found enteroviral RNA in 50% of patient muscle samples but only 10% of controls [8]. Other studies, mostly in the 1980s and 1990s also reported association with enterovirus and myalgic encephalomyelitis, either by antibody or PCR [9, 10, 11].

In an sad but not unexpected turn of events Chia details one his old teachers at the NIH had a study which “dediscovered” the enteroviral findings but only looked in blood [Note: I could not find the specific study he was referring to on pubmed.gov, if anyone knows please message me or leave a comment]–a critical and invalidating flaw:

“They tested the plasma. But this isn’t in the plasma. (…) Viruses live in the cells. This is not HIV. Even, we’re lucky that HIV [you] can find in the blood.” [4; time: 37:45]

One interesting thing about potential enterovirus infection in ME is that a phylogenetic analysis by DN Galbraith, CN Narn, and GB Clements showed 19/20 of the enteroviral infections in ME patients were distinct suggesting that a novel family of enteroviruses is responsible for many cases of ME and explaining the relatively modest findings of investigations looking at specific (and significantly, known) enterovirus types such as Coxsackie in ME patients [11].

Lastly, many patients and researchers may want to read an excellent review of enterovirus and ME by well-known researcher Maureen Hanson and Adam O’Neal [12]. In short, the case for enteroviruses as casual pathogen’s is surprisingly strong and much stronger than the shockingly low-research interest.

In my opinion, the low research interest can mostly be explained by three factors:

- Researchers tend to pursue their pet theories and rarely link up for big collaborative projects

- Finding enteroviruses in tissue is more labor-intensive than looking in blood

- The low status of myalgic encephalomyelitis as an area of medical investigation (despite the gargantuan disease burden and increased mortality!).

Factor 3 in particular means there is less money which further disincentivizes researchers from performing costly collaborations or undertaking intensive projects outside their areas of focus. This forms a sociopolitical “negative feedback loop” where research questions which are technically difficult to answer are simply not explored.

I would recommend that anyone (and hopefully any researcher) who is interested in having a strong overview of enteroviral research in myalgic encephalomyelitis read Hanson and O’Neal’s review the full text of which is freely available [12]. Their extensive citations were very helpful to me in writing this article.

Another review on enterovirus and ME I would recommend was written by Chia in 2005 [13] and it too is available online.

Where are the therapeutics?

While John Chia has talked to drug companies about developing a treatment to enterovirus he reports that the companies, though impressed with his research, tend to forgot enteroviruses later on. This is a fundamental problem mentioned earlier, ME is treated by researchers, companies and the federal agencies as a small problem whereas any honest evaluation of the numbers of people sick and degree of illness would indicate not only is it not a small problem but it is a very large problem.

Even by comparison to a recent problem like COVID-19, ME is very far behind as COVID already has antisera, monoclonal antibodies, broad-spectrum antivirals and, of course, vaccines.

The current desperate lack of therapeutics is one area where the NIH and CDC must take responsibility for fouling up the early investigation of ME in the late 80s and early 90s [14] with the irresponsible promotion of psychogenic theories by several of their researchers such as William Reeves and Stephen Straus and the criminal diversion of congressional money away from “CFS” to study “vague issues of fatigue” unrelated to the disease. [14, 15]

Chia’s thoughts on the relation of Herpesvirus Reactivations to Enterovirus

Chia believes HHV-6 and EBV and other Herpesviruses which have associated with myalgic encephalomyelitis represent reactivations due to the immune system being impaired by the primary enterovirus infection and he explained this by analogy to HIV which leads to the reactivations of many pathogens including Herpesviruses [4, 1 hr, 14 minutes ].

If this analogy is a good one, some of the reactivated viruses could nevertheless be important in explaining specific symptoms of myalgic encephalomyelitis–despite not being the causal pathogen.

What is the relation of enteroviral persistence to other findings such as circulatory system abnormalities and metabolic derangements?

It seems to me if one assumes that the theory of enteroviral persistence is correct the question becomes how to explain the symptoms and bodily derangements we with myalgic encephalomyelitis experience? One way to look at this in more specific terms is to ask how would a chronic enteroviral viral infection (presumably at a low level of replication since the + and – strands were found in the same ratio [10] ) explain other well known findings?

I think some of the most solid are the circulatory system findings: of reduced blood volume [16, 17, 18], the findings of abnormally prolonged vasodilation by acetylcholine [19]. diminished red blood cell deformability [20], and abnormal reduction in cerebral blood flow following orthostatic challenge [21]. Another area where is substantial evidence of abnormality is derangement of cell metabolism [22, 23, 24].

Assuming a smoldering enteroviral infection is the root cause, a most obvious way to explain the circulatory and metabolic findings would be that the EV infection induces a strong inflammatory response including cytokines which cause increased microvascular permeability and blood loss and cytokines which inhibit cellular metabolism as part of an antiviral response. Of course, I am sure there are other ways to explain everything together–but this most obvious path merits investigation!

Signs of a deranged, or exhausted, immune response are another group of findings that many of us are familiar with. In brief, these include:

- proteomic markers indicative of B-cell infection and proliferation driven by autoimmunity or infection [25]

- altered NK cell cytotoxicity; as well as altered NK cell gene expression and cell markers [26-29]

- increased neutrophil apoptosis [30]

- increased oxidative stress [31]

- some cytokines are also increased in certain subsets or perhaps at certain stages of disease [32, 33]

- the cytokine pattern late in the disease is different, possibly due to immune exhaustion [32, 33].

- HHV-6 reactivation has been found at high percentages in the epidemic form [34]

If there is a chronic enteroviral infection then a constant immune response not only makes sense but hopefully, being grounded by a known cause, can be better understood and manipulated. And the signs of immune exhaustion all can be better explained if there is an infection the immune system cannot clear, but by virtue of continually responding to has triggered deleterious secondary effects–whether those are alterations in cell metabolism or induction/promotion of anergy.

Other findings which are of note are findings of increased cardiolipin related lipids in the blood [35], another sign of mitochondrial stress, and the cleaved RNase L antiviral pathway [36, 37] and an increase in 30-130 nm extracellular vesicles with signs of cytokine dysregulation [38]. (obviously this list is not exhaustive)

Lastly, Erik Johnson has accumulated evidence [39,40] that sick-building syndrome, most-likely caused by mold was an important factor at several sites of the Lake Tahoe Outbreak of 1984-5. If environmental toxins were present and suppressing the immune system that means (at the least) people in an area with an outbreak of viral illness would have been likely to experience more severe disease.

More Personal Comments and Thoughts on RNase L and Enteroviral Persistence via DS-RNA.

Chia’s work is extremely impressive. The mechanism for viral persistence, ds-RNA, which he posits (and which is supported by one study [10] ) reminded me of work by Kenny De Meirleir and Robert Suhadolnik showing that in CFS RNase L is cleaved as a result of defective activation by the 2′-5′ Oligoadenylate Synthetase [37, 41].

RNase L cleaves double stranded RNA and if its activation is defective, as has been shown in myalgic encephalomyelitis, that immediately suggests a possible mechanism of viral persistence. It is very tempting to wonder if the enteroviruses associated with ME can induce the repression of RNase L? Or perhaps if a subset of the population has a defective RNase L pathway and this puts them at increased risk of a chronic persistent enteroviral infection of the type Chia describes? This areas of research remain to be connected but to me it seems obvious an attempt should be made to connect them or put them in context of each other.

In light of Chia’s discoveries several things remain. First, hopefully Chia can publish his experiments with isolated virus and SCID mice. Secondly, any attempt to assign a causal pathogen to myalgic encephalomyelitis (or a large subset of it), such as enteroviruses, must be replicated by other scientists. The fact that researchers in Great Britain were finding enterovirus in ME patients in the 1990s (before funding stopped–presumably due to the UK political class’s embrace of the biopsychosocial model) adds further credence to the theory that enteroviruses are involved in the causation of myalgic encephalomyelitis.

Thirdly, the onus is on the NIH, CDC, and other myalgic encephalomyelitis researchers to follow-up on Chia’s discoveries and the model of enteroviral persistence as the main driver of disease in ME. Since these viruses are found in tissues rather than blood this will require effort and money…but that is no excuse. Not only we patients, but the general public is owed an honest account. To take the most recent example, think of how many people have been condemned to long-haul COVID because myalgic encephalomyelitis was never seriously investigated by our federal health authorities beyond vague victim-blaming soliloquies? (Stuffing an entire disease, and an entire population of your fellow citizens, in the waste-basket has had tragic consequences…)

If you would like to support Chia’s vital research donate to the Enterovirus Foundation [42], or lobby your local and state governments and Congress.

Citations

- Wells AI and Coyne CB. “Life cycle of an enterovirus”. En.Wikipedia.Org, 2021, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Viruses-11-00460-g002.png.

- “Koch’s Postulates – Wikipedia”. En.Wikipedia.Org, 2021, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Koch%27s_postulates.

- Chia JK, Chia AY. Chronic fatigue syndrome is associated with chronic enterovirus infection of the stomach. J Clin Pathol. 2008 Jan;61(1):43-8. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2007.050054. Epub 2007 Sep 13. PMID: 17872383.

- Proal, Amy. Amy Proal interview of John Chia. (26:00 m) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LSucgoEvoUQ&t=1584s

- John Chia DW, Chia A, El-Habbal R. Chronic enterovirus (EV) infection in a patient with myalgic encephalomyelitis / chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS). Clin Virol Pathol Anal. (2015). Available online at: https://authorzilla.com/KgmXg/19-international-picornavirus-meeting-final-programme.html ; pg. 133/228 (accessed Dec. 7, 2021).

- Dowsett EG, Ramsay AM, McCartney RA, Bell EJ. Myalgic encephalomyelitis–a persistent enteroviral infection?. Postgrad Med J. 1990;66(777):526-530. doi:10.1136/pgmj.66.777.526

- Hyde, Byron. Understanding Myalgic Encephalomyelitis. Nightingale Foundation, 2021, pp. 52-53. https://www.amazon.com/Understanding-Myalgic-Encephalomyelitis-Byron-Hyde/dp/1989442102/

- Gow JW, Behan WM, Clements GB, Woodall C, Riding M, Behan PO. Enteroviral RNA sequences detected by polymerase chain reaction in muscle of patients with postviral fatigue syndrome. BMJ. 1991 Mar 23;302(6778):692-6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.302.6778.692. PMID: 1850635; PMCID: PMC1669122.

- Fegan KG, Behan PO, Bell EJ. Myalgic encephalomyelitis–report of an epidemic. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1983;33(251):335-337.

- Cunningham L, Bowles NE, Lane RJ, Dubowitz V, Archard LC. Persistence of enteroviral RNA in chronic fatigue syndrome is associated with the abnormal production of equal amounts of positive and negative strands of enteroviral RNA. J Gen Virol. 1990;71 ( Pt 6):1399-1402. doi:10.1099/0022-1317-71-6-1399

- Galbraith DN, Nairn C, Clements GB. Phylogenetic analysis of short enteroviral sequences from patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. J Gen Virol. 1995;76 ( Pt 7):1701-1707. doi:10.1099/0022-1317-76-7-1701

- O’Neal AJ, Hanson MR. The Enterovirus Theory of Disease Etiology in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: A Critical Review. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:688486. Published 2021 Jun 18. doi:10.3389/fmed.2021.688486

- Chia JK. The role of enterovirus in chronic fatigue syndrome. J Clin Pathol. 2005;58(11):1126-1132. doi:10.1136/jcp.2004.020255

- Strauss, Valeria. “Audit Shows CDC Misled Congress About Funds”. The Washington Post, 1999, https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/national/daily/may99/cdc0528.htm. Accessed 7 Dec 2021.

- Johnson, Hillary. Osler’s Web. Iuniverse, 2006. https://www.amazon.com/Oslers-Web-Labyrinth-Syndrome-Epidemic/dp/051770353X/

- Streeten DH, Bell DS. Circulating blood volume in chronic fatigue syndrome. J Chronic Fatigue Syndr. 1998; 4: 3-11

- Streeten DH, Thomas D, Bell DS. The roles of orthostatic hypotension, orthostatic tachycardia, and subnormal erythrocyte volume in the pathogenesis of the chronic fatigue syndrome. Am J Med Sci. 2000;320(1):1-8. doi:10.1097/00000441-200007000-00001

- van Campen CLMC, Rowe PC, Visser FC. Blood Volume Status in ME/CFS Correlates With the Presence or Absence of Orthostatic Symptoms: Preliminary Results. Front Pediatr. 2018;6:352. Published 2018 Nov 15. doi:10.3389/fped.2018.00352

- Khan F, Spence V, Kennedy G, Belch JJ. Prolonged acetylcholine-induced vasodilatation in the peripheral microcirculation of patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging. 2003;23(5):282-285. doi:10.1046/j.1475-097x.2003.00511.x

- Saha AK, Schmidt BR, Wilhelmy J, et al. Red blood cell deformability is diminished in patients with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2019;71(1):113-116. doi:10.3233/CH-180469

- van Campen CLMC, Rowe PC, Visser FC. Cerebral Blood Flow Is Reduced in Severe Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Patients During Mild Orthostatic Stress Testing: An Exploratory Study at 20 Degrees of Head-Up Tilt Testing. Healthcare (Basel). 2020;8(2):169. Published 2020 Jun 13. doi:10.3390/healthcare8020169

- Naviaux RK, Naviaux JC, Li K, et al. Metabolic features of chronic fatigue syndrome [published correction appears in Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017 May 2;114(18):E3749]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(37):E5472-E5480. doi:10.1073/pnas.1607571113

- McGregor NR, Armstrong CW, Lewis DP, Gooley PR. Post-Exertional Malaise Is Associated with Hypermetabolism, Hypoacetylation and Purine Metabolism Deregulation in ME/CFS Cases. Diagnostics (Basel). 2019;9(3):70. Published 2019 Jul 4. doi:10.3390/diagnostics9030070

- Hoel F, Hoel A, Pettersen IK, et al. A map of metabolic phenotypes in patients with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. JCI Insight. 2021;6(16):e149217. Published 2021 Aug 23. doi:10.1172/jci.insight.149217

- Milivojevic M, Che X, Bateman L, et al. Plasma proteomic profiling suggests an association between antigen driven clonal B cell expansion and ME/CFS. PLoS One. 2020;15(7):e0236148. Published 2020 Jul 21. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0236148

- Fletcher MA, Zeng XR, Maher K, et al. Biomarkers in chronic fatigue syndrome: evaluation of natural killer cell function and dipeptidyl peptidase IV/CD26. PLoS One. 2010;5(5):e10817. Published 2010 May 25. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0010817

- Chacko A, Staines DR, Johnston SC, Marshall-Gradisnik SM. Dysregulation of Protein Kinase Gene Expression in NK Cells from Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalomyelitis Patients. Gene Regul Syst Bio. 2016;10:85-93. Published 2016 Aug 28. doi:10.4137/GRSB.S40036

- Huth TK, Brenu EW, Ramos S, et al. Pilot Study of Natural Killer Cells in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalomyelitis and Multiple Sclerosis. Scand J Immunol. 2016;83(1):44-51. doi:10.1111/sji.12388

- Eaton-Fitch N, du Preez S, Cabanas H, Staines D, Marshall-Gradisnik S. A systematic review of natural killer cells profile and cytotoxic function in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Syst Rev. 2019;8(1):279. Published 2019 Nov 14. doi:10.1186/s13643-019-1202-6

- Kennedy G, Spence V, Underwood C, Belch JJ. Increased neutrophil apoptosis in chronic fatigue syndrome. J Clin Pathol. 2004;57(8):891-893. doi:10.1136/jcp.2003.015511

- Kennedy G, Spence VA, McLaren M, Hill A, Underwood C, Belch JJ. Oxidative stress levels are raised in chronic fatigue syndrome and are associated with clinical symptoms. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;39(5):584-589. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.04.020

- Russell L, Broderick G, Taylor R, et al. Illness progression in chronic fatigue syndrome: a shifting immune baseline. BMC Immunol. 2016;17:3. Published 2016 Mar 10. doi:10.1186/s12865-016-0142-3

- Hornig M, Montoya JG, Klimas NG, et al. Distinct plasma immune signatures in ME/CFS are present early in the course of illness. Sci Adv. 2015;1(1):e1400121. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1400121

- Buchwald D, Cheney PR, Peterson DL, et al. A chronic illness characterized by fatigue, neurologic and immunologic disorders, and active human herpesvirus type 6 infection. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116(2):103-113. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-116-2-103

- Hokama Y, Empey-Campora C, Hara C, et al. Acute phase phospholipids related to the cardiolipin of mitochondria in the sera of patients with chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), chronic Ciguatera fish poisoning (CCFP), and other diseases attributed to chemicals, Gulf War, and marine toxins. J Clin Lab Anal. 2008;22(2):99-105. doi:10.1002/jcla.20217

- Suhadolnik RJ, Reichenbach NL, Hitzges P, et al. Changes in the 2-5A synthetase/RNase L antiviral pathway in a controlled clinical trial with poly(I)-poly(C12U) in chronic fatigue syndrome. In Vivo. 1994;8(4):599-604.

- Suhadolnik RJ, Peterson DL, O’Brien K, et al. Biochemical evidence for a novel low molecular weight 2-5A-dependent RNase L in chronic fatigue syndrome. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 1997;17(7):377-385. doi:10.1089/jir.1997.17.377

- Giloteaux L, O’Neal A, Castro-Marrero J, Levine SM, Hanson MR. Cytokine profiling of extracellular vesicles isolated from plasma in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: a pilot study. J Transl Med. 2020;18(1):387. Published 2020 Oct 12. doi:10.1186/s12967-020-02560-0

- Johnson, Erik. “Mystery Disease Hits Three Teachers”. Youtube.Com, 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-EXxnhRm4CA . (Accessed Dec. 20, 2021).

- Johnson, Erik. “Stachybotrys Chartarum At Ground Zero For Chronic Fatigue Syndrome”. Youtube, 2020, https://youtu.be/tUl19NZzoYE . (Accessed Dec. 20, 2021).

- Nijs J, De Meirleir K. Impairments of the 2-5A synthetase/RNase L pathway in chronic fatigue syndrome. In Vivo. 2005;19(6):1013-1021.

- Enterovirus Foundation. https://www.enterovirusfoundation.org/overview . (Accessed Dec. 20, 2021).

Thank you for putting this together with links to citations. It is eye opening to see so much information about enteroviruses put in one place.

I’m glad you found it helpful Colleen. It is surprising to me how little known (at least in the USA) the enteroviral theory of myalgic encephalomyelitis is, especially considering it is one of the oldest and most substantiated theories of causation.

Hopefully this post will go a way towards changing that.

This is really eye-opening. I have several abnormal cardiolipin tests, so that part was interesting.

What method does Dr. Chia used to take tissue samples from patients, and is it something that could be easily replicated?

This is an excellent and concise argument explaining why we need more investigation of enteroviruses in the ME population. Thank you!

I think one of the main methods he used was biopsy of the antrum of the stomach and then staining for VP1 (an enteroviral protein) and testing for viral RNA.

“patients with CFS underwent upper GI endoscopies and antrum biopsies.”

Chia JK, Chia AY. Chronic fatigue syndrome is associated with chronic enterovirus infection of the stomach. J Clin Pathol. 2008 Jan;61(1):43-8. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2007.050054. Epub 2007 Sep 13. PMID: 17872383.

In the interview he also mentioned using neutralizing antibody titers by ARUP labs. (Time 13:40 – 15:00 )

Great delivery. Outstanding arguments. Keep up the great effort.